The story has become a part of family history, a familiar anecdote used to tease: My mother met my father when he was her teacher.

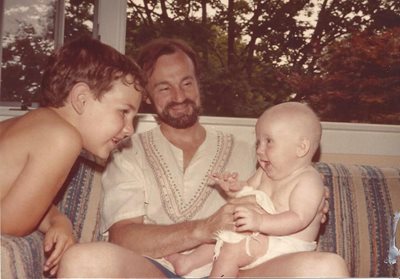

This isn’t entirely true. My mother was a proctor in college and my father led a course on psychology. A proper gentleman, he waited until the end of the school year to ask her out. There’s nothing scandalous about how they met. Growing up, however, my brother and sister and I loved to poke fun at this early courtship, imagining our doe-eyed mother stealing glances at our side-burned father. Over dinners, in long car rides, we asked them to tell the story again and again. This story became shorthand for describing my parents.

Education has always been a central focal point of our family. My father went on to earn his doctorate in educational psychology, teaching for as long he could until the demands of three children forced him into the more lucrative arms of the private sector. My mother, after raising the three of us out of infancy, became an elementary school teacher, later earning a Master’s in education. All the while, education, curiosity and an enthusiastic love for learning were emphasized every day. Our house was full of books, worn National Geographics and nightly documentaries on PBS. My brother, sister and I were taken to hear Beethoven and Brahms at the symphony, Sousa at professional marching band shows (our father’s favorite), then, when we were older, a trip to New York to see a lavish and unforgettable performance of La Bohème at the Met.

Education has always been a central focal point of our family. My father went on to earn his doctorate in educational psychology, teaching for as long he could until the demands of three children forced him into the more lucrative arms of the private sector. My mother, after raising the three of us out of infancy, became an elementary school teacher, later earning a Master’s in education. All the while, education, curiosity and an enthusiastic love for learning were emphasized every day. Our house was full of books, worn National Geographics and nightly documentaries on PBS. My brother, sister and I were taken to hear Beethoven and Brahms at the symphony, Sousa at professional marching band shows (our father’s favorite), then, when we were older, a trip to New York to see a lavish and unforgettable performance of La Bohème at the Met.

I’m telling you all this to give you a small idea of what we lost.

In 2015, while I was living in San Francisco, nearly 2,000 miles away from my father, he called and told me, in a voice that did not quite conceal his anxiety, in a voice that would begin to betray him within a year, that he had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. I tried to act surprised; the signs had been accumulating for years.

More than 5 million people in the U.S. are living with Alzheimer’s, and by 2050, there will be approximately 14 million living with the disease. Much of this growth is due to the fact that every 65 seconds — about the time it takes most people to brush their teeth — someone else develops the disease.

And Alzheimer’s currently has no cure. Diagnostic tests are improving and studies are ongoing, but the disease remains inscrutable. Rather than this being a discouraging fact, I want it to be a call to arms.

Something has to be done, and it is something anyone can do.

The Walk to End Alzheimer’s is the world’s largest event to raise awareness and funds for Alzheimer’s care, support and research. The money raised goes toward the global scientific research that is so critical to finding a cure, toward legislation that mandates a national plan for fighting Alzheimer’s and toward policies that call for additional increases in federal funding. In addition, this helps the Alzheimer’s Association provide nationwide support groups, a 24/7 Helpline and countless other educational initiatives. In short, it is simply the best way to make a difference toward eliminating the disease. And it’s something my mom and dad will be doing together.

Some of my favorite memories of my father involve words. The most infamous is of the dictionary (a red Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate edition) he kept at arm’s length beside the dinner table. Each night, he would say some unfamiliar word, look us in the eye, lean over his plate and demand we tell him what it meant. If we failed, the dictionary would appear and the definition would be read out loud.

As we grew older and more experienced, we would sometimes try to see how good he was at his own game. We would look up an obscure word and then wait for the dinnertime conversation to present us with the right opportunity to slip it in. Invariably, he would not only know what our word meant, but would then double the stakes and ask us to spell it. If we failed, the dictionary would appear and the proper spelling would be read out loud.

As we grew older and more experienced, we would sometimes try to see how good he was at his own game. We would look up an obscure word and then wait for the dinnertime conversation to present us with the right opportunity to slip it in. Invariably, he would not only know what our word meant, but would then double the stakes and ask us to spell it. If we failed, the dictionary would appear and the proper spelling would be read out loud.

His belief in the importance of being able to describe the world in all its accurate detail translated beyond just words. Influenced by his own father, a talented pianist, he had played the trombone since he was in high school and worked hard to share his same musical passion with each of his children. He purchased an upright piano, bought us music lessons and encouraged us to join the band. As we practiced, he would often stop whatever he was doing to listen, point out mistakes, whistle what he thought of as the correct melody or pitch back to us, or yell out — loudly, enthusiastically — when we got it right.

At the time, in the heady days of youth and adolescence, I often thought this interest intrusive and cloying. But looking back, how can I not see the unbridled love? The hours he’d spend sitting beside me, humming a rhythm, as I worked out a new piano piece. The advice he’d offer as I began playing the trumpet, forming my embouchure, playing in an ensemble for the first time. He wanted the best for us. He always did.

My father is still with us. He has difficulty with his sentences, gets confused more easily and will sometimes get frustrated at his diminishing abilities, but he’s there. The laugh that he filled the house with throughout my childhood, the laugh that is buoyant and sonorous and almost an object unto itself, still occasionally emerges.

So does his mischievousness, a tendency that once prevented me from ever taking long showers for fear of him sneaking up and throwing a glass of cold water over the curtain, but that now manifests itself as a gentle poke from his finger, a silly face shared across the room. He’s still there.

This summer, my father and mother will fly out to visit my wife and me and to meet their newest granddaughter. I couldn’t be happier that my father will be able to see my daughter, will have the chance to pick her up and maybe even make her laugh, but I know this moment will be a sad one for me as well. He’s already lost many of his best memories, forgotten old friends and coworkers, the trips he’s taken, the places he’s loved.

It might as well be said — it won’t be long until he begins to forget the rest: the stories we still recall for him, our own faces, us. Then he’ll become a story himself, a part of our history that I’ll be telling my daughter one day. Until that time, we are still here, too. We are still fighting, we are still learning … we are still loving each other.

About the Author: David Young’s parents Mary and Phil Young will be taking part in the 2018 Walk to End Alzheimer’s on October 20 at Palo Alto College as part of team Young at Heart. David lives in Raleigh with his wife Elizabeth and their daughter June. They will be walking in the Raleigh Walk to End Alzheimer's on September 15.

Related articles: