My mother's memory loss first became apparent in 2009, when my parents came to visit my weekend house in the Catskills over the Fourth of July. She told a funny story—not unusual, as she was a legendary storyteller. But just seconds after she landed the punch line, she launched into the same story again, verbatim, from the beginning, with no awareness that she had just told the same anecdote.

When she went home to Maryland, a neurologist diagnosed her with "mild cognitive impairment."

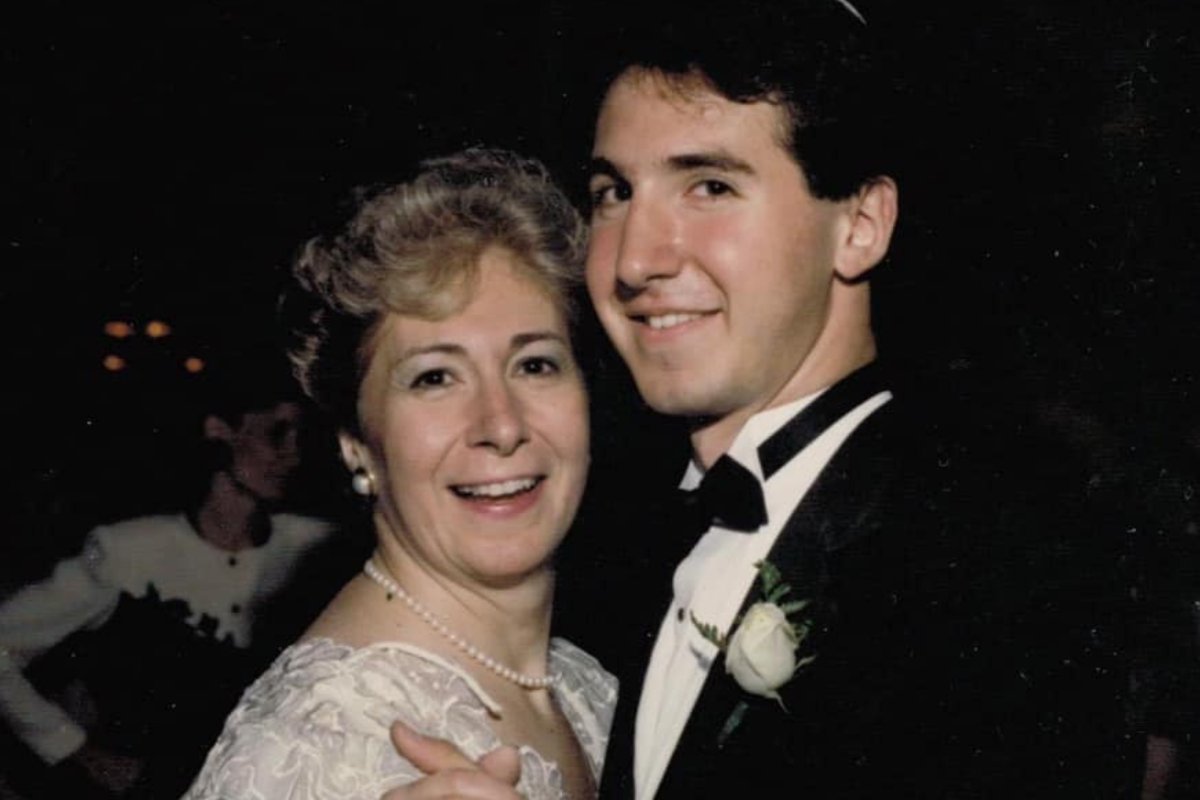

My mother and I have always been close, and even though I lived hundreds of miles away in New York City, we spoke every morning. I could follow her decline on a constant basis through these chats. At first, it was nothing major: She'd repeat herself, get lost in the middle of a thought or forget what she'd done the night before. Eventually, she lost the ability to have meaningful conversations; she couldn't follow the news, or recall the plot of the movie she'd just seen, or remember where I lived or how old I was. Still, while this was disconcerting, it wasn't alarming. Her decline was gradual—"mild," as the neurologist would have it.

After about six years, however, things changed. Her decline became more dramatic: She got lost driving to the house she'd lived in for more than 40 years. She didn't recognize her own clothes, her own bedroom, her own husband. She couldn't tell if I was her son or her husband or her grandson, or what decade it was.

The more confused she became, the more agitated and frustrated she got, and the more she lashed out at people around her. She'd scream at my father for no reason, or cry on the phone to me out of sheer confusion. She started packing to "go home" to her childhood home in Jersey City, waiting for her mother to come pick her up, but the thing she packed were arbitrary—a cutting board, my father's sweaters, a box of rotini pasta, a stapler—and her mother had been dead for decades, something else she'd forgotten.

As her condition progressed, and as her "mild cognitive impairment" segued into Alzheimer's disease, caring for her became a full-time job.

My father hired a driver to take her to a social group for people with Alzheimer's every weekday, so he could go to work. He found an aide to sit with her after the group, until he got home, to keep her out of the kitchen; she was prone to "making dinner" out of raw meat and detergent, snacking on cat food, or putting flammable items in the oven. But it still wasn't enough to keep her safe: One summer evening, after the aide had left, my mother put on a winter coat and sneaked out the door, walking down their street and up the next hilly block until she fainted from the heat and exertion, falling face-first into the pavement. When neighbors came to check on her, bruised and scraped, she didn't know her name or where she lived, so they called 911. By the time my father found her, an ambulance was already on its way. So, my college-aged nephew moved in to keep an eye on his grandmother the rest of the time, to make sure she didn't wander off, fall down, or hurt herself again.

Even with help, caring for my mother was primarily my father's job, and it was taking its toll on him. Time he might have used to work, or exercise, or see friends was now spent watching her to make sure she was safe, all day and all night. Physically and emotionally, he was stretched almost to the breaking point.

I raised the subject of moving her to a full-time care facility, but he wasn't ready to discuss it.

One man understood our family's whole story: Jim ran the social group my mother attended, and also facilitated a support group for caregivers that my father attended.

Jim was at my parents' house once when I was visiting. He asked me how my father was coping.

"He's having a hard time," I acknowledged, "but he's determined to take care of Mom himself, at home, as long as he can."

"Right," said Jim. Then he looked at me and posed a question I didn't see coming: "Why?"

I was caught off-guard. Why was my father planning to take care of my mother as long as he could? Because that's what a good husband does. What a good caregiver does. What a good person does.

What kind of question was that?

Jim explained: Alzheimer's isn't like a broken arm; it doesn't get better after a few difficult weeks. It gets worse, then worse still, until—for most people—living at home simply isn't an option. At some point it's not safe for the person who has the disease, or the other people in the house.

"What your dad is saying when he says that," Jim clarified, "is one of two things: He's either going to do it until he is completely exhausted, and he's simply unable to care for her; or he's going to do it until she has a crisis that puts her in danger, and he's forced to put her in a home. What I'm asking is: Why? If we know she'll need to move eventually, why not do it before one—or both—of those terrible things happens?"

I wish I could say that we took Jim's advice. But like most families, we kept my mom at home as long as we could—until my father was, in fact, physically and emotionally exhausted, and my mother had a series of small crises, leading up to one big emergency where she could have burned the house down with my father asleep upstairs.

Finally, seven years after her diagnosis and a year after my conversation with Jim, we moved her into a home—the move we all knew would come eventually.

My father had been apprehensive about the move, worried that my mother would understand what was happening and would resent him for "giving up" on her. But by this point, her Alzheimer's was so advanced that she didn't seem to notice the move at all.

The three of us arrived at the facility, where a staffer greeted her with open arms; my mother opened her arms in return, not realizing this was a stranger. When the staffer asked my mother if she liked coffee, my mother nodded. "Well, we're making some inside," she said, and guided my mother into the door. And just like that, without a fight or an unkind word to my father, she was gone, never to return home, or even mention her home of more than forty years again.

My story is hardly unique. According to a 2022 special report from the Alzheimer's Association, more than 11 million Americans—family members and friends, many of whom are seniors themselves—are taking care of someone with Alzheimer's "in the community," providing, on average, more than 27 hours a week of unpaid help with tasks like eating, bathing, getting dressed, and using the restroom. One study cited in the report showed that 86 percent of caregivers have been providing support for more than a year, another that 57 percent have been doing so for more than four years. The Alzheimer's Association data also revealed that 59 percent of caregivers report high levels of emotional stress, and 38 percent say the same about physical stress.

While I was writing a family memoir about my mother's decline from Alzheimer's, I spoke with many people who've been through similar things. The more people I've spoken to, the more I've seen the wisdom of Jim's words.

Ask caregivers or other relatives who are further along this journey: Knowing what you know now, what would you have done differently? The answers are all variations on a theme: I would have gotten more help, sooner.

My father told me that, looking back, he would have moved my mother at least six months earlier—maybe a full year. My mother would have been better off, and so would my father.

It's never easy to make these decisions. In some families, people disagree about "next steps." Even though we—my father, my siblings, my aunt—all agreed that a home would be the best place for Mom, the big question was timing. When would we know it was time to move? In the absence of "a sign," we waited, and waited, all the while watching my father grow more and more weary.

Sometimes it's also not possible; facilities are expensive and have long waiting lists. But Jim's advice remains solid: Don't wait for a crisis. Get more help, sooner—from friends, family, health care workers, charitable organizations, or government programs. Anyone who can ease your load in the short term will likely make you a better caregiver in the long term.

If you think doing it all yourself as long as you possibly can is the heroic thing to do, the moral thing to do, the most loving thing to do, the only "right" thing to do, ask yourself the hardest question of all: Why?

Wayne Hoffman is the author of the true-crime family memoir The End of Her: Racing Against Alzheimer's to Solve a Murder. Visit waynehoffmanwriter.com or follow him on Instagram @waynehoffmanwriter.

All views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.