- What Is Dementia?

- What Is Alzheimer's?

- 10 Symptoms and Signs

- Brain Tour

- 7 Stages

- I Have Alzheimer's

- Caring for Someone

- Research

- Message Boards

Take our Brain Tour

See how Alzheimer's affects the brain.

- START TOUR

Alzheimer's and Dementia in Canada

Over 747,000 Canadians are living with Alzheimer's or another dementia. Worldwide, at least 44 million people are living with dementia—more than the total population of Canada—making the disease a global health crisis that must be addressed.

A diagnosis of Alzheimer’s is life changing for the person with the disease, as well as their family and friends, but information and support are available. No one has to face Alzheimer’s disease or another dementia alone.

About Alzheimer’s and Dementia

Alzheimer's disease is the most common type of dementia, an overall term for conditions that occur when the brain no longer functions properly. Alzheimer’s causes problems with memory, thinking and behavior. In the early stage, dementia symptoms may be minimal, but as the disease causes more damage to the brain, symptoms worsen. The rate at which the disease progresses is different for everyone, but on average, people with Alzheimer’s live for eight years after symptoms begin.

While there are currently no treatments to stop Alzheimer’s disease from progressing, there are medications to treat dementia symptoms. In the past three decades, dementia research has provided a much deeper understanding of how Alzheimer’s affects the brain. Today, researchers are continuing to look for more effective treatments and a cure, as well as ways to prevent Alzheimer’s and improve brain health.

Learn more about the basics of Alzheimer’s and the stages of Alzheimer’s.

Memory Loss & Other Symptoms of Alzheimer’s

Trouble with memory—specifically difficulty recalling information that has recently been learned—is often the first symptom of Alzheimer’s disease.

As we grow older, our brains change, and we may have occasional problems remembering certain details. However, Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias cause memory loss and other symptoms serious enough to interfere with life on day-to-day basis. These symptoms are not a natural part of getting older.

Alzheimer's is not the only cause of memory loss. Many people have trouble with memory — this does NOT mean they have Alzheimer's. There are many different causes of memory loss. If you or a loved one is experiencing symptoms of dementia, it is best to visit a doctor so the cause can be determined.

In addition to memory loss, symptoms of Alzheimer’s include:

- Trouble completing tasks that were once easy.

- Difficulty solving problems.

- Changes in mood or personality; withdrawing from friends and family.

- Problems with communication, either written or spoken.

- Confusion about places, people and events.

- Visual changes, such trouble understanding images.

Family and friends may notice the symptoms of Alzheimer’s and other progressive dementias before the person experiencing these changes. If you or someone you know is experiencing possible symptoms of dementia, it is important to seek a medical evaluation to find the cause.

Visit our Know the 10 Early Signs and Symptoms of Alzheimer’s page to learn more about the difference between ordinary age-related changes to memory and the brain and the symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

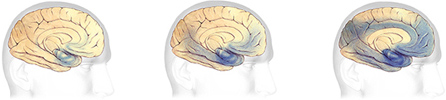

Alzheimer’s and the Brain

Brain cells in the hippocampus, the part of the brain associated with learning, are often the first to be damaged by Alzheimer’s. This is why memory loss is often the first symptom of the disease.

Take our interactive Brain Tour to see how Alzheimer’s affects brain health.

TAKE THE BRAIN TOUR

TAKE THE BRAIN TOUR

Risk factors for Alzheimer’s

While we do not yet understand all the reasons some people develop Alzheimer’s disease while others do not, research has given us a better understanding of which factors put someone at a higher risk.

- Age.

Advancing age is the greatest risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s disease. Once someone reaches the age of 65, the risk of developing Alzheimer’s doubles every five years.

Although far less common, younger-onset Alzheimer’s (also known as early-onset Alzheimer’s) affects people younger than 65. It is estimated that up to 5 percent of people with Alzheimer’s have younger-onset disease. Younger-onset Alzheimer’s is often misdiagnosed.

- Family Members with Alzheimer’s. If your parent or sibling develops Alzheimer’s, you are more likely to develop the disease than someone who does not have a first-degree relative with Alzheimer’s. Scientists do not completely understand what causes Alzheimer’s to run in families, but genetics, environmental factors and lifestyle may all play a part.

- Genetics.

Researchers have identified several gene variants that increase the chance of developing Alzheimer’s disease. The APOE-e4 gene is the most common risk gene associated with Alzheimer’s; it is estimated to play a role in as many as one-quarter of Alzheimer’s cases.

Deterministic genes are different than risk genes in that they guarantee someone will develop a disease.

The only known cause of Alzheimer’s is from inheriting a deterministic gene. Alzheimer’s caused by a deterministic gene is rare, and likely occurs in less than 1 percent of Alzheimer’s cases. When a deterministic gene causes Alzheimer’s, it is called “autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease (ADAD).”

- Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI).

The symptoms of MCI include changes in the ability to think, but these symptoms do not interfere with everyday life and are not as severe as those caused by Alzheimer’s or other progressive dementias. Having MCI, particularly MCI that involves memory problems, increases the risk of developing Alzheimer’s and other dementias. However, MCI does not always progress. In some cases, it reverses or remains stable.

- Cardiovascular Disease.

Research suggests that brain health is closely related to heart and blood vessel health. The brain gets the oxygen and nutrients needed to function normally from blood, and the heart is responsible for pumping blood to the brain. Therefore, factors that cause cardiovascular disease also may be linked to a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s and other dementias, including smoking, obesity, diabetes, and high cholesterol and high blood pressure in midlife.

- Education and Alzheimer’s.

Studies have linked fewer years of formal education with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s and other dementias. There is not a clear reason for this association, but some scientists believe more years of formal education may help increase connections between neurons, allowing the brain to use alternative routes of neuron-to-neuron communication when changes related to Alzheimer’s and other dementias occur.

- Traumatic Brain Injury. The risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias increases after a moderate or severe traumatic brain injury, such as a blow to the head or injury of the skull that causes amnesia or loss of consciousness for more than 30 minutes. Fifty percent of traumatic brain injuries are caused by motor vehicle accidents. Individuals who sustain repeated brain injuries, such as athletes and those in combat, are also at a higher risk of developing dementia and impairment of thinking skills.

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease

There is not a simple test to tell us if someone has Alzheimer’s. Diagnosis requires a comprehensive medical evaluation, which may include:

Is there an Alzheimer’s test?There is no simple way to detect Alzheimer’s. Diagnosis requires a complete medical exam. Blood tests, mental status tests and brain imaging may be used to determine the cause of symptoms.

- Your family’s medical history

- A neurological exam

- Cognitive tests to evaluate memory and thinking

- Blood tests (to rule out other possible causes of symptoms

- Brain imaging

While doctors can usually determine if someone has dementia, it may be more difficult to distinguish what type of dementia. Misdiagnosis is more common with younger-onset Alzheimer’s.

Less than half of the people with dementia in England, Wales and Northern Ireland receive a diagnosis. Receiving an accurate diagnosis earlier in the disease process is important because it allows:

- A higher likelihood of benefiting from available treatments, which can improve quality of life

- The opportunity to receive support services

- A chance to participate in clinical trials and studies

- An opportunity to express wishes regarding future care and living arrangements

- Time to put financial and legal plans in place

Alzheimer’s Treatment and Support

While there are currently no treatments available to slow or stop the brain damage caused by Alzheimer’s disease, several medications can temporarily help improve the symptoms of dementia for some people. These medications work by increasing neurotransmitters in the brain. To see a list of medications approved to treat Alzheimer's in Canada, visit Alzheimer's Society of Canada's website.

Help Is Available

Find local programs and services through the Alzheimer's Society of Canada.

Researchers continue to search for ways to better treat Alzheimer's and other progressive dementias. Currently, dozens of therapies and pharmacologic treatments that focus on stopping the brain cell death associated with Alzheimer's are underway.

In addition, having support systems in place and the use of non-pharmacologic behavioral interventions can improve quality of life for both people with dementia and their caregivers and families. This includes:

- Treatment of co-existing medical conditions

- Coordination of care among health care professionals

- Participation in activities, which can improve mood

- Behavioral interventions (to help with common changes, such as aggression, sleep issues and agitation)

- Education about the disease

- Building a care team for support

Caregiving

Providing care for someone with Alzheimer’s disease or another dementia can be both rewarding and challenging. In the early stages of dementia, a person may remain independent and need very little care. However, as the disease progresses, care needs will intensify, eventually leading to a need for round-the-clock assistance.

We often hear from caregivers and family members that one of the most upsetting aspects of Alzheimer’s is the changes in behavior it causes. Many resources are available to help caregivers know what to expect and how to adapt during the early, middle and late stage of the disease.

Learn more about caring for someone with Alzheimer’s.

How We Help

As the world’s leading voluntary health organization dedicated to Alzheimer’s care, support and research, the Alzheimer’s Association strives to make life better for all those facing Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. We fund critical research; provide education and resources; raise awareness; and advocate in partnership with government, private and nonprofit organizations to work toward our vision of a world without Alzheimer’s disease.