Triple Your Impact This Holiday Season

Triple Your Impact This Holiday Season

Celebrate the holidays with a year-end gift that can go 3x as far to help provide care and support to the millions affected by Alzheimer's disease, and to advance critical research. But please hurry — this 3x Match Challenge ends soon.

Donate NowFive things we want you to know

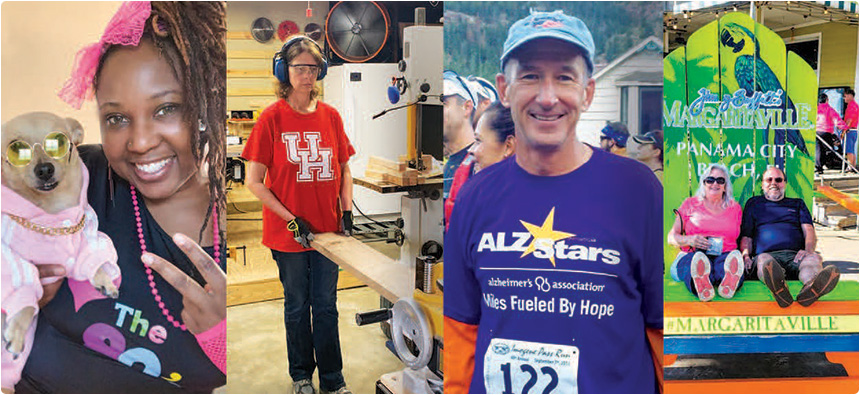

Living with Alzheimer's is a constant, ever-evolving challenge, and the many misconceptions about the disease only add to the stigma and social disconnect. Here, four members of the Alzheimer's Association National Early-Stage Advisory Group — people living with Alzheimer's or another dementia who help raise awareness of the disease — share five things they want everyone to know about living with it.

1. Some days are better than others — and that's OK.

Everyone has good and bad days, but for those living with dementia an "off" day means difficulties with everyday life. Validate the person's efforts to be successful and understand that some tasks or conversations may need to be picked up at another time.

"There are good days and bad days, but that doesn't make us bad people. That just means we're human," says Ricci Sanchez, who was diagnosed with younger-onset Alzheimer's in 2019 at age 56. "It's about making daily experiences as valuable as possible and not feeling ashamed if you have a less-than-stellar day."

"I live moment by moment," says Nia Mostacero, who was diagnosed with younger-onset Alzheimer's at age 42. "Just because you're having a conversation with me today and I seem alert doesn't mean tomorrow is going to be the same. It's just the way it goes."

"We can be much harder on ourselves than we should be," says Mike Zuendel, who was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to Alzheimer's disease in 2020 at age 66. "It's important to look for small moments of gratitude."

"We can be much harder on ourselves than we should be," says Mike Zuendel, who was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to Alzheimer's disease in 2020 at age 66. "It's important to look for small moments of gratitude."

2. You don't need to fear us.

Much of the stigma surrounding Alzheimer's is rooted in fear. If you know someone living with the disease, take the time to learn about it. Knowledge can create empathy and shows you care about the person.

Know what to expect

An Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis is life-changing. You can take an empowering first step by learning more about the changes you may experience and what to do next to move forward with your life.

"Don't be ignorant or in denial about the disease," says Bart Brammer, who is living with Alzheimer's. "Get educated about it. Some people might be afraid to learn what it really is or feel uncomfortable talking about it, but we need everyone in order to fight this."

"Sometimes I feel like I have to prove my case, that I'm both a functioning adult but also living with a terminal illness," Mike says. "People don't understand how I can be both. I feel almost defensive about it, but I know it's a lack of education."

3. Don't make assumptions based on our diagnosis.

Comments like "You don't look like you have dementia" or "You can't have Alzheimer's — you seem fine" might be well-intentioned, but they expose a longstanding myth that people living with the disease look and act a certain way. Especially in the early stage of the disease, people can maintain their independence with adjustments.

"An Alzheimer's diagnosis is life-changing, but it's not the end," Mike says. "Don't count us out."

"People assume you can't do anything when you're living with the disease," Bart says. "Yes, we can. We might have to adjust our routines, but we can still live happy, healthy lives. Our bucket lists aren't empty."

"We might have some deficits, some behavioral or memory problems, but our lives don't stop," Nia says.

"We might have some deficits, some behavioral or memory problems, but our lives don't stop," Nia says.

4. No two journeys are the same.

People living with Alzheimer's will experience the disease in different ways. Recognize and respect how each individual feels and what they need, even if it's the opposite of someone else living with dementia.

"If you've met one person living with dementia, you've only met one person with dementia," Nia says. "Almost everything about us is different: Our chemical and biological makeups, our progression and our experiences."

"We might have some commonalities but not nearly as many as people think," Bart says.

"We might have some commonalities but not nearly as many as people think," Bart says.

"No matter what, each of us deserves grace and peace," Ricci says.

5. Talk to us directly.

Don't talk around the person living with the disease. Engage with them the way you always have. It might take them longer to respond or you may need to repeat yourself, but they still need and want to communicate and feel included.

"Even if it feels difficult to talk to me, it really isn't," Ricci says. "I think people feel uncertain, and I'm respectful of the fact that this is a tough diagnosis and it's hard to see someone not articulate as well as they used to. But I'd much rather you let me talk and help clarify things that don't make sense rather than ignoring me altogether."

"Even if it feels difficult to talk to me, it really isn't," Ricci says. "I think people feel uncertain, and I'm respectful of the fact that this is a tough diagnosis and it's hard to see someone not articulate as well as they used to. But I'd much rather you let me talk and help clarify things that don't make sense rather than ignoring me altogether."

Read More ALZ Magazine Articles

Blog posts

I Have Something to Tell You

Blog posts

Dementia Through a Different Lens

Blog posts

Time to Talk

The first survivor of Alzheimer's is out there, but we won't get there without you.

Donate Now

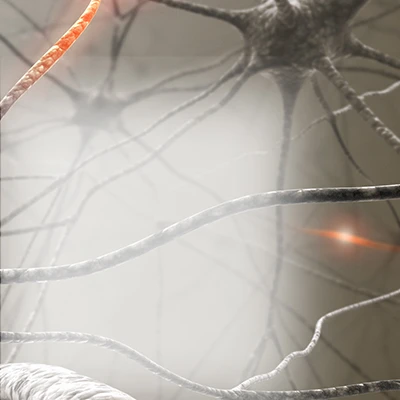

Learn how Alzheimer’s disease affects the brain.

Take the Brain Tour