Double Your Love. Double Your Impact.

Double Your Love. Double Your Impact.

Help provide 2x the care and support for millions affected by Alzheimer’s and advance research to bring us closer to a cure. Make a gift during our Double the Love 2x Match now.

Donate NowRare gene variant could lead to new Alzheimer’s treatments

A small group of people worldwide are born with rare gene variants that guarantee they’ll develop younger-onset Alzheimer’s.

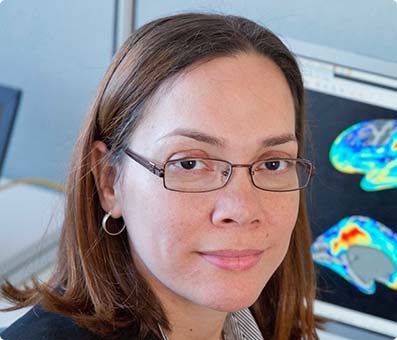

Because of this destiny, a group of dedicated families in Colombia who carry a variant of the PSEN-1 gene — which causes Alzheimer’s — are working with researchers to find a way to unlock the mysteries of the disease. Scientists like Yakeel T. Quiroz, Ph.D., associate professor in the Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, are studying this unique family cohort in the hope they can get ahead of the disease and find a way to prevent or slow it in all populations.

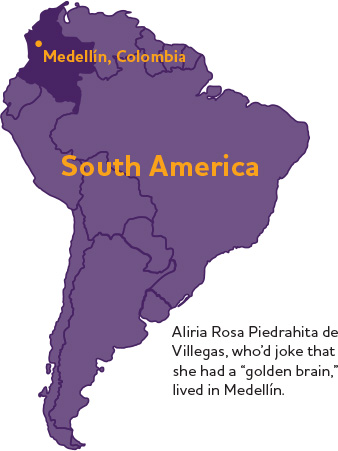

Recent work with family members carrying the rare PSEN-1 gene variant has led to a breakthrough discovery — Aliria Rosa Piedrahita de Villegas, a woman in her 70s from Medellín, Colombia, who’d joke that she had a “golden brain.” Despite carrying the same PSEN-1 gene variant, Aliria appeared to be resistant to developing Alzheimer’s. Understanding how this could happen, Quiroz says, could potentially help millions facing the disease around the world.

Recent work with family members carrying the rare PSEN-1 gene variant has led to a breakthrough discovery — Aliria Rosa Piedrahita de Villegas, a woman in her 70s from Medellín, Colombia, who’d joke that she had a “golden brain.” Despite carrying the same PSEN-1 gene variant, Aliria appeared to be resistant to developing Alzheimer’s. Understanding how this could happen, Quiroz says, could potentially help millions facing the disease around the world.

“This opens a new door for Alzheimer’s research,” says Quiroz, whose work is partially funded by an Alzheimer’s Association grant. “And through that door are new opportunities for treatments.”

Variant stuns researchers

For decades, researchers have been studying 6,000 members of the Colombian family cohort looking for insights into Alzheimer’s. As part of this effort they met Aliria, who carried the PSEN-1 gene variant that causes cognitive impairment to develop around age 44 in her family. But miraculously, Aliria didn’t show any signs of impairment until age 72 — nearly three decades after the typical age of onset for carriers of this variant.

Further study showed Aliria also had two copies of another rare variant, this time on the APOE gene, known as Christchurch. Researchers believe the Christchurch variant — named after the city in New Zealand where it was first discovered — helped protect Aliria’s brain and drastically slowed the progression of Alzheimer’s.

Deterministic genes guarantee Alzheimer's

Members of Aliria’s familial group develop Alzheimer’s due to deterministic genes. Having deterministic genes is extremely rare — accounting for only 1% or less of all Alzheimer’s cases worldwide — but this field of study has provided important insights into how Alzheimer’s develops in all people.

Is Alzheimer's genetic?

When diseases like Alzheimer's tend to run in families, either genetics (hereditary factors) or environmental factors — or both — may play a role.

In recent years, researchers have increased their focus on studying Alzheimer’s in its earliest stages in an effort to stop the disease before it is too late to treat. Since people with deterministic genes know they will develop Alzheimer’s with almost 100% certainty, they can participate in research well before they have obvious symptoms of the disease.

“It is like being able to look into the future. Our work with this family cohort allows us to track those earliest changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease and identify how those changes happen over time,” Quiroz says. “This will help us identify, in people beyond those in Colombia, who may be at risk and who may be more resistant to Alzheimer’s, as well as learn which biomarkers are better predictors of disease progression.”

Christchurch offers protection

After flying Aliria to Massachusetts General Hospital for more extensive examinations, brain scans showed that despite having extremely high levels of beta-amyloid — sticky plaques considered a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease — the Christchurch gene variant had protected her from neurodegeneration and developing tau tangles, abnormal forms of the protein tau that build in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s.

Researchers suggest that the presence of two copies of the Christchurch variant may have slowed the progression of Alzheimer’s biology in Aliria’s brain. They theorize that the variant may have a protective effect by preventing the accumulation of tau tangles and associated cell death.

Quiroz and other researchers are now working on developing an Alzheimer’s treatment that can replicate the protective actions and effects of the Christchurch variant.

“Aliria gives me a lot of hope. Delaying onset for 30 years is very ambitious, but anything we can do to delay cognitive decline would get us closer to our goal, and it is something that Aliria showed is possible,” Quiroz says.

A race against time

While slowing or stopping Alzheimer’s for all people is the goal, Quiroz also has a more personal motivation for her work. Having met and studied children, teens and young adults from the Colombian family cohort with the PSEN-1 gene variant, Quiroz feels she is in a race against time.

While slowing or stopping Alzheimer’s for all people is the goal, Quiroz also has a more personal motivation for her work. Having met and studied children, teens and young adults from the Colombian family cohort with the PSEN-1 gene variant, Quiroz feels she is in a race against time.

“For me, the challenge is to find a treatment for them before they make it to their 40s and develop Alzheimer’s,” she says.

While an important discovery, Aliria’s gene variation is one case of a truly exceptional individual. Additional research is needed to understand if the Christchurch variant can be translated into an effective strategy for treatment.

The Colombian families who are participating in this critical research are trying to do just that — helping scientists pave the way toward new effective treatments for all people.

Clinical Trials Are Vital to Fighting Alzheimer's

Recruiting and retaining clinical trial participants is the greatest obstacle, other than funding, to developing the next generation of Alzheimer's treatments. Individuals living with dementia, caregivers and healthy volunteers are all needed to participate in Alzheimer's and dementia studies. Alzheimer’s Association TrialMatch® is a free clinical trials matching service that connects individuals living with Alzheimer's, caregivers and healthy volunteers to current research studies.

Read More ALZ Magazine Articles

Blog posts

More Women Get Alzheimer’s Than Men. Why?

The first survivor of Alzheimer's is out there, but we won't get there without you.

Donate Now

Learn how Alzheimer’s disease affects the brain.

Take the Brain Tour