Make 2x the Impact Now

Make 2x the Impact Now

Our March Mission Match is underway, but not for long. Your gift by March 10 can go twice as far to advance research and help provide care and support for those living with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers.

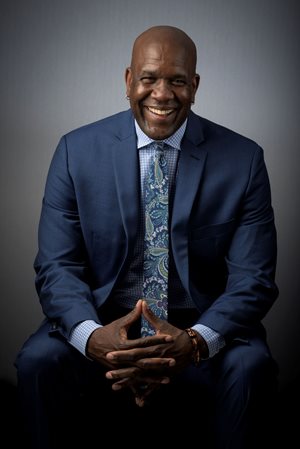

Give NowRobert W. Turner II, Ph.D., is co-principal investigator for the Black Men's Brain Health Emerging Scholars program, a former football player and a caregiver for his dad, who is living with Alzheimer’s. He talks to us about his focus on education around Alzheimer’s disease for retired Black athletes.

Dr. Turner, tell us about your personal connection to Alzheimer's disease and your caregiving experience.

Alzheimer’s hit close to home on the paternal side of my family. My dad is the third of his siblings to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or another dementia, after my aunts Thelma and Eleanor. I’ve seen how Alzheimer’s can affect multiple generations all at once. I also saw how my aunts — who were single, adult women who had no one else in their lives caring for them — needed family to step up to advocate for them.

The youngest of nine children, my dad always took on a lot of responsibility. His sister came to live with my parents as they were about to start enjoying retirement. Unfortunately, my mom had kidney disease, and on the heels of her kidney transplant, my dad developed mild cognitive impairment (MCI), later diagnosed as Alzheimer's, which progressed quickly into the moderate middle stage of the disease.

It takes so much to care for someone. Today, we’re blessed to have a home health care worker, and me and my siblings are caregivers for our parents much of the time.

It is very personal when you see this disease at work, and what a huge challenge it can be. It's hard for parents to allow their children to help them when they are so used to doing everything themselves. I understand the plight of family members who need to communicate with parents or grandparents to say: “You took care of me. Now I need to take care of you.”

Today, me and one of my brothers are very much in charge of leading our parents' care, and I won't lie — it has been a real challenge, and a process. Once you recognize that, it helps you be a better caregiver, and better to yourself. You can move from crisis management mode and transition to your new reality.

How has your career trajectory shaped you, from student athlete to gerontologist?

Being a Black man has affected me more than anything in my sports or education background. It is the one constant thing that shapes me as a person.

Black men make up 70% of NFL players, with nearly 60% of NCAA Division 1 college football players also being Black. These are spaces where people have expectations for you, and you feel like you belong. But that isn’t how the rest of the world works. I have found myself in experiences and situations where I am the only Black man present, and I have felt like an outsider.

In some respects, that challenge was the most beneficial part of graduate school. Transitioning to life after football and learning about everything from CTE and brain injuries to Alzheimer’s and other dementia also got me thinking about how caregiving shaped my experience and the way I approach life.

Being a Black man in the research space also made me painfully aware that I am sometimes the only one traversing these spaces. I played football for 16 years; when I was no longer playing, I had a bit of an identity crisis. ‘Who am I outside of football, and what do I do beyond that?’ When I started graduate school, I studied the life course of athletes to answer that exact question: Why do some athletes struggle in their transition to life after football? I focus on this in my book, “Not For Long: The Life and Career of the NFL Athlete.”

Being a Black man in the research space also made me painfully aware that I am sometimes the only one traversing these spaces. I played football for 16 years; when I was no longer playing, I had a bit of an identity crisis. ‘Who am I outside of football, and what do I do beyond that?’ When I started graduate school, I studied the life course of athletes to answer that exact question: Why do some athletes struggle in their transition to life after football? I focus on this in my book, “Not For Long: The Life and Career of the NFL Athlete.”

As a Black man, there have been many spaces where I was told I should be grateful for the opportunity I was given — and that I would need to find a whole lot of strength to navigate my way. This all shaped my education, which got me to start thinking about caregiving and how best to support other families. I first started studying brain injury in relation to concussions and CTE, which led me to further studies around dementia.

While I was training as a sociologist, Keith E. Whitfield, Ph.D., president of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), got me interested in becoming a gerontologist. He was the one who first got me involved in the Alzheimer's Association International Society to Advance Alzheimer's Research and Treatment (ISTAART), which convenes the global Alzheimer's and dementia science community. By sharing knowledge and collaborating with others in the field, I began to think about ways to advance research to help former athletes navigate the complicated world of Alzheimer’s. I truly feel like I am part of a team again.

Today, I’m fortunate to have the support of my family and friends and from my colleagues in gerontology. I found a supportive academic and professional space where people are so dedicated to solving the issues related to Alzheimer’s. They give me the tools to be successful, because the more successful I am as an individual, the more successful we are collectively.

As a former NFL player, what is the biggest impact being made with the National Football League Alumni Association?

The best thing happening now is that former athletes are beginning to ask questions in ways they haven't asked them in the past. There is still a lot of distrust in the medical field from the Black Americans, so when it comes to support services, the communication has to come from people who are trusted. Athletes want help, and want to know that if they begin down a road, they will be able to continue down it, including getting properly tested for dementia.

I worked with Dr. Carl Hill, chief diversity, equity and inclusion officer of the Alzheimer's Association, to look at how important information is being disseminated; how to get more people involved in clinical trials; and the need to let people know about the support and resources available through the Association. My mission is to help players become more involved in their own health journey and to get facts from a medical and neuropsychological perspective. You can't be empowered unless you have information and knowledge, and know how to access it.

Brad Edwards, CEO, and Bart Oates, president of the NFL Alumni Association, and our team are working to enhance the overall health and productive acuity of retired players, their families, and their communities. For the most part, NFL athletes are no different from any other people who may not know about Alzheimer’s until it hits home. We know the partnership between the NFL Alumni Asssociation and the Alzheimer's Association is important in order to spread awareness. And because these athletes can help share this information with their fellow athletes and others in need, they have the power to be ambassadors for this cause.

Hearing from NFL alumni in their 50s who don't know what they’re going to do to help their family if dementia enters their lives is a reminder that everyone must feel empowered to ask more questions. The NFL Alumni Association wants former athletes to understand the realities of Alzheimer's, starting with the signs of the disease. From there, they can develop strategies to plan and take care of themselves going forward.

Tell us about your work with the Black Men's Brain Health Emerging Scholars program.

If it weren't for the support of the Alzheimer's Association and the leadership of Dr. Maria Carrillo, chief science officer, we wouldn't be able to be doing what we are doing right now, including partnering for the Black Men’s Brain Health (BMBH) Conference, which convenes scientists and community leaders to increase the representation of Black men in brain science research and to reduce brain health disparities.

We are aimed at growing culturally-sensitive research and building a registry for Black men to be involved in biomedical research through our the BMBH Emerging Scholars program. The program will support 30 early and mid-career investigators examining brain aging among Black men. Each scholar will use community-based research methods to recruit registry participants during their 15-month involvement with the program.

I am deeply immersed in the Black community and our unique challenges. By using a health disparities research framework, we can better educate and recruit underrepresented clinical trial participants in communities that have a history of distrust in the medical field. It is our hope that the involvement of NFL Alumni Association athletes means that potential Black male clinical trial participants can become inspired to become involved, too. Football fans feel a sense of brotherhood, and that is why voices of retired players matter so much.

What are your hopes for the future?

A world without Alzheimer's and a world without health inequalities is my hope. With so many underrepresented populations and health outcomes on the line, we have to be looking ahead. The future of America is going to be much more diverse, and the reduction of health inequalities will benefit all populations.

We must recognize that if any group suffers, we all suffer. It is important to make sure Black men don't get left behind when it comes to research, clinical trials and opportunities to learn. Education about the management of one's overall health and the effects of impact sports is the first step to understanding, and then taking action.

Learn more about the Alzheimer’s Association partnership with the NFL Alumni Association.

About: Dr. Robert W. Turner II is an Assistant Professor in the department of Clinical Research and Leadership at The George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Science.

About: Dr. Robert W. Turner II is an Assistant Professor in the department of Clinical Research and Leadership at The George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Science.

Lead researcher for the Brain Health & Aging Study, Dr. Turner is an author, researcher, and former NFL player. His National Institute on Aging (NIA) funded K01 award examines psychosocial and neurocognitive risk and protective factors, accelerated cognitive aging and mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI) among former NCAA Division I and former NFL athletes. Visit Dr. Turner on Twitter.

The first survivor of Alzheimer's is out there, but we won't get there without you.

Donate Now

Learn how Alzheimer’s disease affects the brain.

Take the Brain Tour