Your Gift Can Make 2x the Impact

Your Gift Can Make 2x the Impact

A gift can go twice as far during our February $100,000 2x Match. Your contribution by Feb. 27 will fuel Alzheimer’s research and help provide essential care and support.

Donate NowHow Advocate Grace Williams Found Her Voice in the Fight to End Alzheimer’s

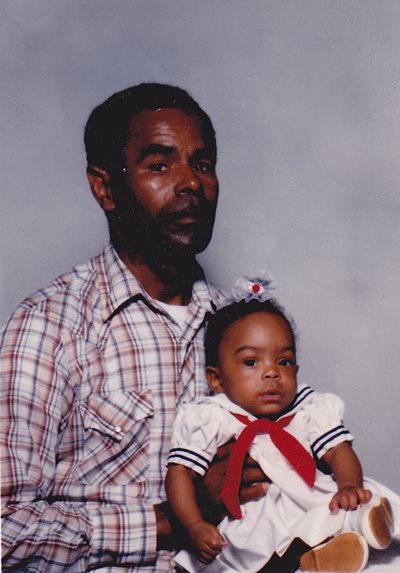

Grace Williams is an Alzheimer’s Association advocate and Alzheimer’s disease researcher. She lost her father to Alzheimer’s, and her paternal grandmother to dementia.

Grace, your father was diagnosed with younger-onset Alzheimer’s disease when you were just 9 years old. What was that experience like?

My dad was 56 years old at the time of his diagnosis, and I didn't understand what the disease was. I was a kid. I was very confused about how to help.

My dad was someone who loved to go to work every morning, and he started every day in this positive, rockstar kind of way. He loved to talk to everyone: at work, at church, even random people at a gas station. So when I noticed that he started having issues talking to people, I knew something was off.

My dad was someone who loved to go to work every morning, and he started every day in this positive, rockstar kind of way. He loved to talk to everyone: at work, at church, even random people at a gas station. So when I noticed that he started having issues talking to people, I knew something was off.

Then came the day we were driving the car, and he stopped at a red light. When the light turned green, he didn’t move. He didn't realize that green meant “Go.” Soon after, he wasn't able to drive at all, an activity that was very important to him.

He enjoyed life so much, and pressed the importance of education, family, travel and connecting with people upon me, things that were always important to him. Alzheimer’s really changed him, and how he interacted with the world.

How did you educate yourself about the disease at that time?

I started doing Internet searches so I could learn more about the brain and find out what was going on in my dad’s brain and overall health. This is what first sparked my interest in neuroscience and biochemistry.

Libraries have always been amazing, full of free, widely-available resources. At age 9, I spent an afternoon on the floor of my local library’s medical section, poring through college and medical school textbooks, looking up phrases like ‘sundowning’ and other terms I had heard mentioned. This was between 1999 and 2000, so I really had to dig.

I wish I had known about resources like the 24/7 Alzheimer’s Association Helpline. Being a young caregiver involves so much responsibility. The roles flip; now you are monitoring your parent’s activities, making sure they are safe and prepared for the future. I want people to know that there are generational resources out there that can help you on your path, a path that is difficult, and one you need to be prepared for. A good place to start is with your local Alzheimer’s Association chapter.

Tell us about how you got involved in the Alzheimer’s cause, and with Alzheimer’s Association advocacy.

I first got involved with the Association through the Walk to End Alzheimer’s, which I have now participated in about 15 times! At the time I got involved, I was in high school, working, prepping to get into college and taking care of my dad, so I couldn’t dedicate as much time as I wanted to the cause.

Then, while I was in college, after getting more involved with the Louisiana Chapter of the Association, I heard people chatting about an advocacy event in D.C. That was when I first learned about the annual AIM Alzheimer’s Association Advocacy Forum, the nation’s premier Alzheimer’s disease advocacy event. Weeks later, I got a call inviting me to attend! I was beyond excited to go to my first Advocacy Forum, where I would be able to share how I was impacted by Alzheimer's disease. I think I cried dozens of times, basically a continuous cry.

Prior to attending the Advocacy Forum, I swore I was the only young person with a parent with this disease. The experience made me realize that I was not alone.

This was the first time I got to tell my story and see young people like me who were impacted by the disease. I spoke with other young advocates about our journey (and missteps) with the disease, and how we remembered our loved ones and told their stories. It was all so cathartic. This group of young advocates sat together for hours, plotting what we wanted to change about how Alzheimer’s is talked about and funded in our country. It was a huge sense of community, full of hopes and plans for making positive change. It was an opportunity for me to talk about my experience — and try to improve outcomes at a policy level, for families like mine.

When I went to my first Forum, I spoke with my representative face-to-face in the very first meeting I had in D.C. There I was, very nervous in a full suit, with my purple folder, a young college student. Once I mentioned the A-word, ‘Alzheimer’s,’ the entire dynamic of the room changed. As I shared my story, the first thing I heard from the people in the room was: “HOW CAN WE HELP?”

Today, sharing my experiences comes more easily. I have practiced what I want to say and how I want to share my personal story. But my reason for being in that room with those policymakers was so much bigger than myself or my family. It was and continues to be for the wider community.

Talk to us about the importance of a support system. How can this change the landscape of someone's journey with the disease?

Alzheimer’s can be such an isolating disease, so having a support system is so important, whether you find it through family and friends, a virtual forum, or resources like the Alzheimer’s Association support groups. The people that you surround yourself with have an impact on the way you communicate and also how you think about the disease.

It’s important for people starting out on this journey to know that over time, the weight gets heavier. Being able to reach out to people and make them aware of your situation is essential, whether you are looking for a sounding board, a prayer partner, or a larger form of support. Support will determine how the disease affects your life, not just physically or mentally, but financially. You must educate yourself about the disease and find the support system that works best for you.

It’s important for people starting out on this journey to know that over time, the weight gets heavier. Being able to reach out to people and make them aware of your situation is essential, whether you are looking for a sounding board, a prayer partner, or a larger form of support. Support will determine how the disease affects your life, not just physically or mentally, but financially. You must educate yourself about the disease and find the support system that works best for you.

Alzheimer’s is a very expensive disease. When I was first dealing with Alzheimer’s over two decades ago, people were losing health care coverage due to preexisting conditions. And as a caregiver, I needed to get my dad to his appointments. I had to miss school, or shifts at work, and not every employer will be understanding about the caregiving demands of this unpredictable disease.

In addition to support, self-care is something I highly recommend. If you aren't able to take care of yourself in a way that preserves your energy, you can't provide the care you need for your loved one. Make connections and build a network. It will alleviate some of the stress and will increase your endurance in this long journey. Alzheimer’s is not a sprint — it’s a marathon.

From your perspective as a researcher, how do you think getting involved in clinical trials helps break stigma around Alzheimer’s and other dementia?

Alzheimer’s is still very stigmatized in Black families. My dad was born in the 1940s and grew up in a segregated education system. And the same was true of health care. When he had spinal meningitis, the first hospital he went to refused to treat him. He faced a lot in the Jim Crow South that affected his everyday life. People who have experienced bias within the health care system still face challenges and barriers today, but this is definitely something that we can improve upon.

For a long time, particularly in the Black and other minority communities, we haven't had the option to opt in when it comes to health care and research. It has been chosen for us. As researchers, care providers and health care professionals, it's important that we approach these situations with humanity, and dignity. If we can provide a support system and a safe environment for people, it may allow them to get involved, and to make a true impact.

For a long time, particularly in the Black and other minority communities, we haven't had the option to opt in when it comes to health care and research. It has been chosen for us. As researchers, care providers and health care professionals, it's important that we approach these situations with humanity, and dignity. If we can provide a support system and a safe environment for people, it may allow them to get involved, and to make a true impact.

Participating in a study or clinical trial is one way to take action in a situation that often makes you feel stuck, or helpless. When you are actively involved in a trial, you get a fuller view of the parameters of the experience. You may not see an immediate result, or any results from a trial, but it can make a difference for the future. It’s empowering to be able to provide an impact for your own life and the lives of others.

How has sharing your personal story affected your life?

Speaking out about my personal experiences has helped me process losing my dad and my grandmother, but it has also given me the opportunity to remember and honor them. After my dad passed, I couldn’t deal with the fact that he was gone. Talking about what happened — and envisioning how I wished things would change for families going forward — helped me find my voice again. Walking the halls of Congress and speaking at town hall meetings, I advocate for legislation that improves quality of life and health care for Alzheimer’s patients.

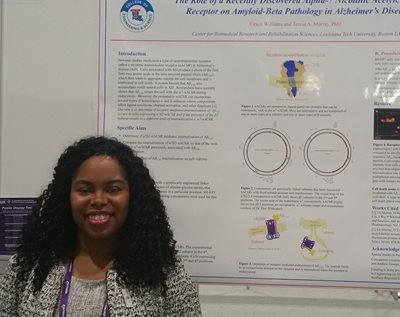

Alzheimer’s will always be a part of my life. But it has also created opportunities for me to help others. My dad always thought I would be a doctor, so working toward my Ph.D. felt like I was making him proud. Today, as a researcher, I am looking to identify a therapeutic target for Alzheimer's treatment. I'm interested in slowing the progression of the disease — or stopping it where it is.

For the past seven months, I have pressed pause on my research in Louisiana to work as an emergency response pandemic worker in a COVID-19 lab. It has been scary seeing the impact of COVID, something that was barely being mentioned in January 2020. By March, labs were shutting down, and it was really concerning, knowing how connected researchers are to their work, and how impactful their work is for medical care and future treatments. Interestingly, the techniques I use in my Alzheimer’s research are perfect for COVID research. My skill set allowed me to get involved, and although it has been a very raw experience, I knew it was essential for me to help.

What gives you hope for the future?

I am inspired by the ferocity of the people who are not only personally affected by Alzheimer’s, but who understand that this disease has become a crisis. As a researcher, seeing the passion and compassion of those setting up a clinical trial and its design — as well the physicians and other researchers dedicated to making strides in the field of Alzheimer's research — gives me hope.

We have millions of Americans who are currently living with Alzheimer's, and I want to make sure that their quality of life is the best it can possibly be while we work towards a cure. As we look to new drugs and new treatments on the horizon, including the potential of a cost-effective blood test that may be used to test whether or not someone may have Alzheimer's, the potential for diagnostic improvements is closer than we think.

We have millions of Americans who are currently living with Alzheimer's, and I want to make sure that their quality of life is the best it can possibly be while we work towards a cure. As we look to new drugs and new treatments on the horizon, including the potential of a cost-effective blood test that may be used to test whether or not someone may have Alzheimer's, the potential for diagnostic improvements is closer than we think.

I feel blessed to have the opportunity to do all the things I do, from my research and advocacy work to what I am doing today during the pandemic. These opportunities have allowed me to honor the two people who had the spirit of community engagement and volunteering in their blood: my dad and grandmother. All I can do is try to embody the things they taught me, and share them with the next generation of young advocates — and all people who are in the fight to end Alzheimer’s.

About: Grace is pursuing her Ph.D. from Louisiana Tech University with a focus on molecular science and nanotechnology. She completed a science policy fellowship in Washington D.C., informing science technology through work in medicine and public policy. She then worked at the USAID, a U.S. government agency that works to end extreme global poverty, focusing on global health. She is an Alzheimer’s Association Congressional Ambassador, advocating for policies and legislation of Association, and a member of the Advisory Board of the Louisiana Chapter of Alzheimer’s Association.

Related Articles

The first survivor of Alzheimer's is out there, but we won't get there without you.

Donate Now

Learn how Alzheimer’s disease affects the brain.

Take the Brain Tour